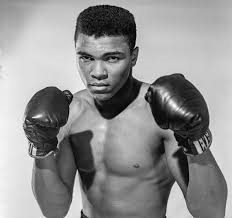

I first became acquainted with the true impact of Muhammad Ali about 20 years ago when I reviewed a one-man play about his life for NAACP’S The Crisis magazine. As a woman raised in a patriarchal household in a country (Liberia) run by proud men, I saw Ali’s pronouncements of his skill and physical beauty as loud-mouthed braggadocio (he was quick to point out it is not bragging if you can back it up, and he ultimately won Olympic gold and held the world Heavyweight Championship three times).

In my then-context men do, they don’t talk. But in the context of Black American life at the time, Ali was larger than life. His bold stance on the Vietnam war echoed the angst of Black soldiers from the founding of America who volunteered for armies that despised them, for freedoms that eluded them.

In the Revolutionary War Black men fought, propelled by the promise of freedom, for both sides. In the Civil War they fought with the Union Army, without proper equipment and for lesser pay than whites—freedom being the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. During the Civil War, they often faced execution or being sold back into slavery if they were caught by the Confederates; their white counterparts, by contrast, were hauled off to squalid prison camps. In these and subsequent wars Black men fought to earn what should have been inalienable rights.

“Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letters, U.S.; let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket,” Frederick Douglass once said, “and there is no power on earth which can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship.”

Fast Forward to the end of World War II: A Tuskegee airman, dressed in his smart military uniform, traveling with his wife, is tossed off a train in the middle of a cornfield after being denied appropriate, non-segregated accommodations. The only thing standing between the airman and an escalation of events that would have cost him his life was the tears of his new bride. The airman? Percy Sutton, legal counsel to Malcolm X and Manhattan’s first Black borough president.

Another post-World War II story: My cousin’s widower enters a store with his cousin, who asks to be served. Both men sport their military uniforms. They are turned down by the clerk, who won’t wait on them because they are Black. The cousin, who has returned home with PTSD, introduces the clerk to his pistol, and is promptly served.

Others, like Isaac Woodard, didn’t triumph in a uniform-provoked altercation. He had his eyes gouged out and was denied medical treatment for two days, lying beaten and bloodied on a jail floor until his frantic family located him. Woodard’s savage attack was evidently part of a surge in violence against Black military men stateside that left them maimed, dead or both the year-plus after the defeat of Hitler. Douglass’s path to citizenship proved dangerous for many Black men who proudly wore the uniform after returning home from a conflict.

For the establishment, Ali calling it like it is on this issue was rattling. They feared his influence on a Black population trained to be cannon fodder in times of military need, and then to return to business as usual after the conflict, living marginalized lives in neglected communities.

Years after his conversion to Islam media outlets, snarling reporters and boxing officials continued to refer to Ali as Cassius Clay, their Toby to his Kunta Kinte. Who did he think he is? Of the Viet Cong Ali famously said, “They never called me nigger, they never lynched me … shoot them for what?….You won’t even stand up for me, for my religious beliefs,” he chastised the American public.

Black troops, rather than being demoralized by his statements, cheered his speaking truth to power; after all, democracy begins at home. Ali would need this support as he was banned from boxing for more than three years, stripped of his boxing titles, and, shades of Paul Robeson, his American passport.

For African Americans, who dined on a steady diet of self hatred, Ali’s pronouncements “I am so pretty” and “I am the greatest,” coupled with his rugged individualism, were like sweet nectar. As we wind up this week of celebrating his life, I hold on to one of the sayings attributed to this extraordinary human being: “Don’t count the days, make the days count.”

Muhammad Ali, father, grandfather, brother, husband, friend, humanitarian, Parkinson’s activist, philanthropist and athlete of the century, you were unapologetically, unequivocally, unabashedly Black. And you sure were pretty.

You must be logged in to post a comment.