I am one of the lucky ones. One of the almost one million African diasporic people who visited Ghana as part of the Year of Return—a campaign designed by the Ghanaian government to invite all Africans home. The indigenous version of the 1619 Project marking 400 years since the first slave was kidnapped in Africa and landed in the Americas. But without any of the controversy of the New York Times series conceived of by African American reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones. This one, the ultimate FUBU project.

Africans who both lost and sold hundreds of thousands of people from the land mass now known as Ghana embraced Black people from all over the world for the Year of Return. “Welcome home, welcome back,” we were told over and over by our gracious hosts. It was as if the entire nation had been trained to receive us—the Africans whose ancestors were snatched up mostly from the Continent’s west coast and then vomited up on the shores of the Americas. The Africans who forged a new language from the hundreds of tongues they brought with them to the new world. The Africans of gumbo and jumping the broom, and quilts and spirituals with directional for those with the courage—and the opportunity—to run toward freedom.

I travelled to the Motherland with 40 other African and Caribbean Americans who entrusted Overton Travel from Mount Vernon with this tenderest of sojourns. We were mostly middle-aged professionals with a sprinkling of those at the beginning and those nearing the end of life. For such a large and at times unwieldy group, we got along famously, for the most part.

There was much at stake as we answered Ghana’s call for reconciliation, historic and cultural celebration—and commerce. So much to dissect about what we were seeing and feeling. We exchanged our impressions with one another on our long bus rides, at meals, and after hours in our hotel rooms.

We had come full circle, and this trip was in some way helping to calm the beating heart of the discomfort of living in lands that have never truly embraced us. For many of us, just being in Ghana was the closure we needed—it brought into focus the identity that we so casually toss around without thinking about it: African American.

In the capital, Accra, we styed at the Mövenpick Ambassador hotel. I immediately fell in love with its African masks, sculptures and fabrics—some 2,500 pieces of Ghanaian art. (I was also partial to the expansive pool, where I took a brief dip between scheduled activities.)

I am not a museum person, but the eponymous Kwame Nkrumah Memorial Park and Mausoleum, dedicated to the celebrated Pan-Africanist and Ghana’s first president, left me with much to ponder about this complex country. The park features sculptures of warriors in an eternal pool, each with his own expressive features.

A sculpture of Nkrumah—which was vandalized when he was deposed in 1966—is on display, his head in one place, and most of his body missing an arm, not too far from it. Now art in itself, the mutilated Nkrumah is leitmotif for a collection of African nation states that became a country, and whose promise in the Western context has never been fully realized. Like Humpty Dumpty who couldn’t be put back together again, neither can the political systems that existed before colonialism. Africans, like African Americans, exist in the in-between.

A 40-minute flight from Accra took us to Tamale in the north. From there we drove to Salaga, a village that was once home to a bustling slave market. There the villagers bathed our feet and apologized to us for slavery. In a chief’s palace in a ceremony that was part kitsch and part solemn we were given new names, which we greedily lapped up—desperate for any connection to this lovely country, to these people with a vibrant culture, their own languages, traceable history and names that tie them all together in a neat bow.

On the coast in Kumasi in the land of the legendary Asante (known in the west as Ashanti), we stayed in my second favorite hotel, the Golden Tulip. The hotel bustled with eager, mostly middle-aged visitors from the African diaspora and young Ghanaian couples adorned with kente wraps tossed carelessly over their squared shoulders, and African prints accessorized with 18K gold jewelry from their earth. Many of the couples were on a night out. I secretly envied their sense of self, their rootedness. They didn’t need warm greetings to assuage their otherness. They didn’t need a campaign to invite them home, they were home.

My tour group eagerly descended upon the world-famous Kente Village moving slowly, shoulder-to-shoulder with other diasporic Africans giddy with the gorgeous purchases we secured with our mediocre bargaining skills. But it was a win-win. Priceless items for us. Good sales for the artisans.

The history of the unbowed, unbroken Asante warriors resonated with me. At the height of the European land grab of the Continent the Asante fought back. After waging war on the British in 1896 the king, Asantehene Agyeman Prempeh I, was captured by them and exiled to the Seychelles. In 1900 his mother, the revered queen Yaa Asantewaa, led troops in battle against the British, who demanded the Golden Stool, a symbol of Asante dynastic power. The queen was eventually captured, also, and exiled to the Seychelles, where she died. The British never secured the stool, which to this day retains its prominence in Asante culture.

Yaa Asentewaa reminds me of Nanny the Maroon, a Jamaican national hero of Asante descent, who led thousands of captured Africans to freedom at the height of slavery. Harriet Tubman, an African American hero of the Underground Railroad, too, was thought to be of Asante descent. If that is so her heritage in part explains her fierceness, her tenacity—and her visions.

In Kumasi, Asante Region, we visited Manhyia Palace Museum, gifted to the Asantehene Agyeman Prempeh I in 1925 by the repentant British. In true Asante fashion the king paid for the building himself to avoid losing face were the British to retract the gift. “Neither a borrower nor a lender be,” is the Shakespeare quote so often used by my paternal grandmother and passed down to my father and then to me. Have your own. Whatever you can’t provide for yourself you don’t need in the first place. The museum celebrates the rich history of the Asante kingdom and includes a range of artifacts, from gold jewelry and royal kente to the television that the king watched with local children.

I had read about how the infamous Elmina slave castle was rank with the blood, sweat and waste of Africans, captured and preserved in the dank recesses of these dungeons. For a time such as this. So we’d witness it. So we’d never forget.

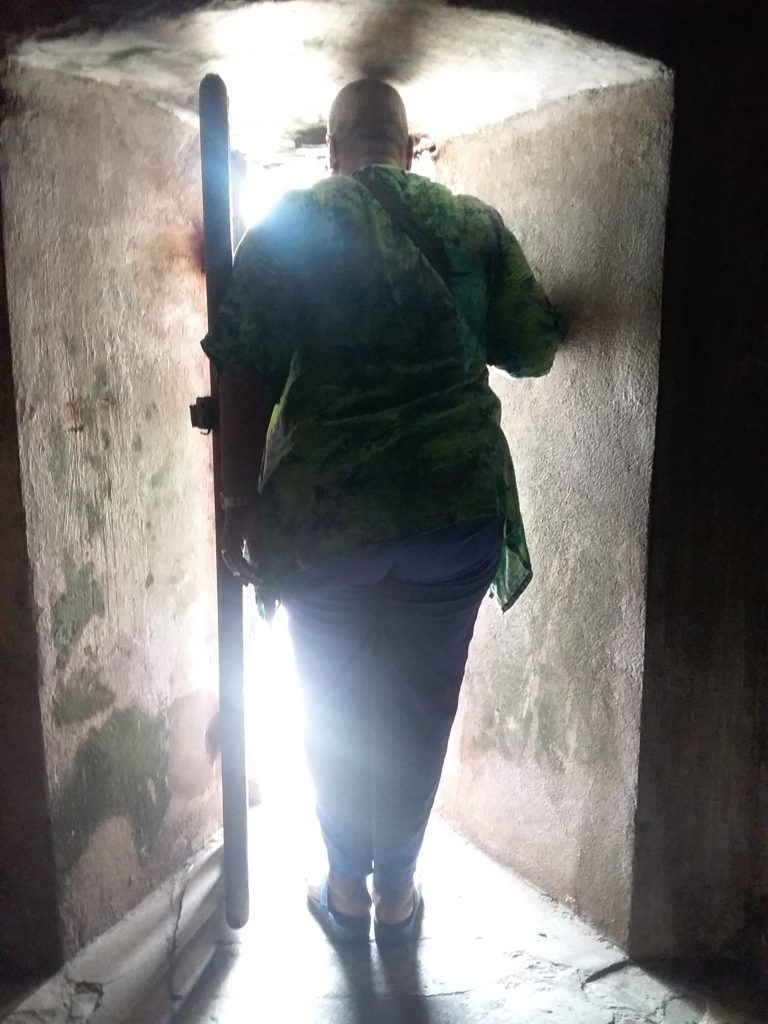

While some of us wept, others peered into the darkness, trying to find our bearings, wincing as we touched the soiled walls. Trying to imagine what it would have been like for them. In an orderly fashion and without a sound from our mute lips, we took turns photographing one another in the Door of No Return, where our ancestors saw African land for the last time before being taken via the Middle Passage to the Americas.

Months later I am still trying to process the Year of Return not just personally, but in terms of the significance of the campaign to the African diaspora in the long term. What would it look like if we truly united to maximize the Continent’s riches on our own behalf?

Before I landed in Ghana, I spent two days in Dubai, which is part of the seven-state United Arab Emirates, a modern, highly functional country built from the desert by nomads. A country that has maximized its oil reserves on behalf of its people. Of the 10 million residents of the Emirates only one million are Emirati. The nine million guest workers support the one million citizens in almost every aspect of the service economy. I thought of Ghana’s oil-rich neighbor Nigeria. I thought of Ghana with oil and Asante-dominated gold mines. What if?

My trip to Ghana was hectic but well worth every (overscheduled) minute. And, by the way, the new name conferred on me? Titiaka. Loose translation: What went before no longer is. Happy New Year, Affirming Community. Happy New Year.

You must be logged in to post a comment.